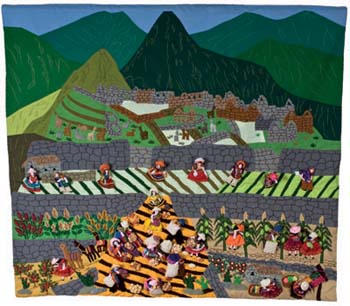

Machu Picchu Farmers

- ca. 2009

- Maria Uyauri (Peruvian 1955-), NOVICA in Association with National Geographic

- Cotton, acrylic and other fibers; wooden toothpicks; wall hanging

84.6 x 98.0 x 4.0 cm., 33-1/4 x 38-5/8 x 1-1/2"

- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2010.8

Essay by Molly Todd, Former Assistant Professor of History

Artist María Uyauri consciously blends past and present in this tapestry. She celebrates key aspects of indigenous life in the Andes: harvesting the staples of maize and potatoes from terraced fields, the use of llamas and alpacas as pack animals as well as sources of wool and meat, and the weaving of colorful fabrics. The terraces where these men and women work have been farmed since the time of the Inca civilization (1200s-1500s). Doña Uyauri celebrates that civilization and its continued heritage by placing her farmers in the shadow of Machu Picchu, a city built at the behest of Inca imperial authorities. The focal point of the background is a mountain soaring more than 2700 meters high; historians believe that Huayna Picchu once housed Incan high priests. Although forever known to locals, Machu Picchu received international attention only in the first decades of the 1900s, when U.S. historian Hiram Bingham "discovered" it. To this day, conflicts continue between the Peruvian government and Yale University, where Dr. Bingham worked, regarding artifacts that Dr. Bingham and his researchers removed from the site. Machu Picchu has been designated a Peruvian Historical Sanctuary and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

A harder to see, yet absolutely crucial part of this piece is the context of genre. Machu Picchu Farmers is part of the arpillera tradition, which first gained international recognition during the 1970s. At that time, women in Chile began gathering in small groups and, using rags and old clothing, created fabric appliqué scenes that depicted the hardships of life under the military dictatorship headed by General Augusto Pinochet Ugarte (1973-1990). They called these pieces arpilleras, or burlaps, for the castoff fabric sacks used as the backing. Their creators became known as arpilleristas; they comprised a social movement that defied the dictatorship in many ways: by simply gathering together in groups (which the military had criminalized); by selling their artwork to help provide for their families during difficult economic times (which directly countered the gendered norms of the regime); and by sending messages to international observers about the disappearances, torture, and assassinations occurring in Chile. (See Augustana's collection of Chilean arpilleras for a sampling of such messages.)

Women in other countries of Latin America soon adopted the arpillera as both a method of protest against violence and repression, and as a means of income. Although the creator of this tapestry no doubt lived through the violence associated with Peru's Sendero Luminoso (Shining Path) insurgency (1980s-early 1990s) and Alberto Fujimori's repressive rule (1990-2000), this particular piece was not necessarily a response to those experiences or a call for international solidarity. Instead, the rather romantic scene of Machu Picchu Farmers, created circa 2009, was probably intended as a means to earn some money. Doña Uyauri was born in Lima in 1955, likely to a family of limited economic means. As a member of a women's support group, she learned the craft and business of arpilleras. Today, she is an independent artisan; with help from her husband and son, she creates pieces with happy themes including festivals, harvests, weddings, and markets.