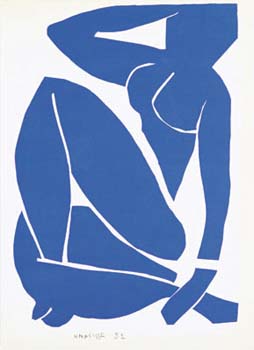

Blue Nude III, or Nu bleu III

- 1952

- Henri Matisse (French 1869-1954)

- Series of 4 lithographs printed by Fernand Mourlot Printers and published 1958 in Verve magazine

35.5 x 26.3 cm., 14 x 10-3/8" sheet

- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2007.8.1a, b

Essay by Noell Birondo, Former Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy

Although Henri Matisse never enjoyed especially good health, he was left chronically bed-ridden later in life, having survived an operation that neither he nor anyone else really expected him to survive. It was then that Matisse began working extensively in colored paper, forgoing the relatively more arduous work of producing paintings on canvas. Matisse himself failed to see any real disconnect between his previous artistic output and this new work in cut paper: he simply referred to this new activity as "painting with scissors." This unique experiment produced a series of remarkable cutouts, including these strikingly sensual, and yet oddly spiritual, Blue Nudes.

The severe abstraction of the Blue Nudes certainly shows a strong continuity with some of Matisse's earlier artistic concerns. Some of his previous work in paint aimed not to depict some particular thing: a specific woman, plant, or fruit, located in a specific time and place. The paintings seem rather to communicate the essence-or the idea-of the things being depicted.

The Blue Nudes certainly manifest that same concern. The images clearly don't depict any specific woman. They aim rather to depict femininity, and especially feminine sensuality, itself. In the original cutouts, and in these lithographs, Matisse offers a purified glimpse of female sensuality, one communicated through his own vision of it.

Those reflections obviously echo two great philosophers in the Western tradition: Plato, from ancient Athens, and Arthur Schopenhauer, from 19th-century Germany.

Plato famously argued that bodily desires provide a stumbling block to any genuine understanding of reality. He thought that appreciating the timeless essence of reality required a distancing of the intellect from the spatiotemporal cares of the body.

Schopenhauer simply extended that line of thought to the realm of art. He claimed that people could never attain genuine understanding-or lasting happiness-as long as they were obsessed by their everyday concerns, by their day-to-day desires. Thus the value of art, as Schopenhauer saw it, lies precisely in its ability to release us from the tyranny of our desires. When we properly confront great art, he thought, our desires evaporate in an appreciation of a true, timeless reality. That possibility explains how the Blue Nudes manage to be both gorgeously sensual and utterly anti-pornographic.

One final reference addresses the obviously spiritual nature of the Blue Nudes. It reports Matisse's own answer-at exactly the time he produced these cutouts-to the question whether he believed in God. "Yes," Matisse wrote, "when I am working."