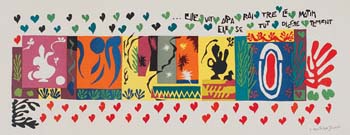

Les Mille et une nuits (The Thousand and One Nights)

- 1950

- Henri Matisse (French 1869-1954)

- Color lithograph

30.6 x 81.0 cm., 12-1/16 x 31-7/8" image

- Gift in Honor of Dr. and Mrs. Thomas William Carter through Drs. Gary and Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2008.21

Essay by Randi Higel, Class of 2008 and Catherine Carter Goebel, Editor

As the leader of the Fauves, French Expressionists, Matisse always demonstrated a remarkable feel for color and pattern, often tinged with sensitivity toward exoticism. This piece is a brilliant mix of vibrant colors, abstract shapes and brash lines. During his recuperation from serious surgery, Matisse fashioned brilliance of necessity and invented a new art form, the cut-out, rooted in a pair of scissors and painted paper.

In June of 1950, Matisse commenced work on a large, twelve-foot panel inspired by the Arabian Nights. This series of stories, originally told in Arabic, began to be collected around 1000 CE and was traditionally said to have been brought together by protagonist Scheherazade. Scheherazade's life was threatened by her new husband, the once cuckolded King Shahryar, who planned to kill all his future wives in the night while they slept. To avoid death, Scheherazade entertained the king for 1001 nights by telling him a different story each night.

Suffering from insomnia following his illness, Matisse perhaps felt a bond with Scheherazade as they both feared the uncertainty of the night. Through strategic placement of subjects, the composition tells an interesting story within its narrative. From left to right, we read a burning Persian lamp, reminiscent of Aladdin's magic lamp, releasing smoke from its spout which leads us to a dancing blue figure, perhaps a genie, as well as to the central panel which indicates the various phases from night to day.

This image is followed by the silhouette of a once burning Persian lamp, now dark and extinguished, while the oval lines and shapes of the final image evoke the morning sunrise. These separate elements within the narrative, placed in consecutive order, tell a new story: a story about the passage of night to day and the queen's relief that she has survived yet another night. The readings might also be interpreted as revealing bits and pieces derived from various Arabian tales. The center of the composition suggests a storm at sea, as in the tales of Sinbad, culminating in the entrance to a cave, like that of Ali Baba, terminating with the dawn, when Scheherazade "falls discreetly silent" (Cowart et al 169). Less is indeed more, perhaps, as one grasps intuitively for greater meaning, fragile and fugitive like the magic from Aladdin's lamp.