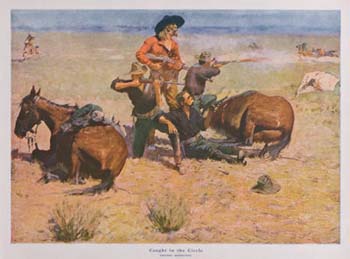

Caught in the Circle

- n.d.

- Frederic Remington (American 1861-1909)

- Lithograph originally published in 1901 as double-page spread, Collier's Weekly

30.2 x 39.7 cm., 11-7/8 x 15-5/8" sheet

- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2010.42

Essay by Jane Simonsen, Associate Professor of History and Women's and Gender Studies

Frederick Remington rose to prominence as a painter and illustrator between 1890 and 1915. His scenes of the ruthless environments and fearless fighters of the American West seemed to contrast mightily with the industrialized East and Midwest, where work was becoming ever more rule-bound and a flood of immigrants seemed to threaten the jobs and cultural supremacy of Euro-Americans. For viewers at the time, Remington's raw West suggested a return to a more natural time, when men were invigorated rather than depleted by their responsibilities. As working-class men felt increasingly unmanned by their dependence on owners' wages and middle-class men bowed to the repetition and femininity associated with desk jobs now often held by women as well, psychologists like G. Stanley Hall argued that boys needed to cultivate their inner "savage self" in order to recover the vigor intrinsic to manhood. Remington's good friend Theodore Roosevelt lauded the healthful effects of the "outdoor life" and rejoiced in the fact that the Spanish-American War of 1898, in addition to catapulting the U.S. onto the world stage as a colonial power, would literally turn boys into men. In his famous 1899 speech, "The Strenuous Life," Roosevelt exhorted Americans that "the timid man, the lazy man, the man who distrusts his country, the over-civilized man, who has lost the great fighting, masterful virtues, the ignorant man, and the man of dull mind.all these, of course, shrink from seeing the nation undertake its new duties." Sternly, he reminded his public that "We do not admire the man of timid peace."

Roosevelt anticipated a new era for America as colonial power, and artists like Remington looked to the American West, a region of earlier conquest by European and later American powers, for inspiration. While, like Roosevelt, Remington was an Easterner—he painted from his New York studio—he regarded the West as a place where men had defined themselves by assuming responsibility in life-and-death situations: fighting Native Americans, fending off a raging bull moose, guarding a precious source of water from competing cattlemen. As an illustrator who created more than 2,500 paintings, drawings, and sculptures, Remington helped to create the "myth of the West"—where the stoic, tragic, gallant cowboy resisted the forces that would confine him—even as it was rapidly disappearing. By the time he painted Caught in the Circle (web gallery 175) in 1914, the so-called "Indian Wars" of the West were over, and the violent confrontations between white and native that had captured the American imagination for well over a century were being replaced by the reality of the cultural conquest of the West. Many Native Americans were confined to reservations, barbed wire criss-crossed the formerly open range, and white and indigenous men alike were more likely to be working-class cogs than heroes of the open range. Remington's paintings, while realistic in their style and detail (Remington began his career as a journalist), are decidedly works of the imagination.