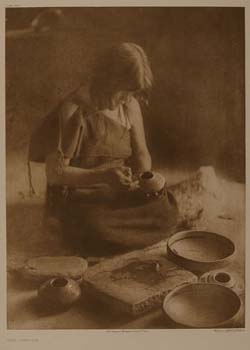

The Potter--Plate 426 [Nampeyo]

- 1922 from 1906 photograph

- Edward Sheriff Curtis (American 1868-1952)

- Photogravure

39.4 x 29.0 cm., 15-1/2 x 11-3/8" image

- The Olson-Brandelle North American Indian Art Collection, Augustana College, 2005.1.26aa

Essay by Adam Kaul, Associate Professor of Anthropology

In this photograph by Edward S. Curtis simply called The Potter, we see a woman at work painting traditional designs on a clay pot. While the image itself seems straightforward, the story behind it is complex. The subject is the famous American Indian potter named Nampeyo. Although she passed away in 1942, she remains one of the best-known Native American potters.

Nampeyo bridged distinct eras in Native American history, from independence to the reservation system. Because she is often credited with introducing Pueblo pottery to tourists and collectors, she also acted as a different kind of bridge, from the Pueble peoples to the dominant culture. Nampeyo is most often associated with the Hopi, an American Indian tribe that is one of a number of related Pueblo cultures whose homelands are found in what is today Arizona and New Mexico. On the surface of this photograph, we simply see Nempeyo sitting and painting a pot, but in that act she also bears the weight of a whole cultural tradition. She embodies the pottery-making of the generations of women who came before her. And her small act creates a gift to the future generations of women who in turn bear the tradition for their daughters.

Given her fame and influence in reviving this art-form, it was no wonder that in 1906 Edward S. Curtis decided to photograph Nampeyo doing something that seems so simple on the surface and yet was in reality so powerful—sitting on a sheepskin spread out across the floor painting a pot. In front of her are several other pots, some finished and others perhaps waiting to be painted. With deft brushstrokes she applies handmade paints to the clay pot in her hand, using a piece of yucca as a brush.

Although part of Curtis' aim was to document what he assumed were vanishing American Indian cultures, there is no doubt that much of his work was purposefully romantic and sentimental, and that he consciously controlled the subject matter of each photograph (Coleman VI). Images like The Potter do not represent candid moments in the lives of American Indians; instead, like a studio artist—or more to the point, like the portait photographer he was—Curtis posed the subjects, carefully chose which objects to include in each image, and actively "directed the scene".