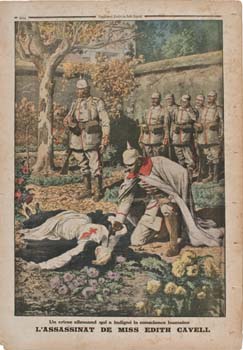

Un Crime Allemand qui a indigné la conscience humaine / L'assassinat de Miss Edith Cavell (The Assassination of Miss Edith Cavell: A German Crime that Outrages the Conscience of Humanity)

- 1915

- Artist undetermined

- Newspaper printed in color, back cover of Le Petit Journal: Supplément Illustré, 7 November 1915

44.9 x 31.4 cm., 17-11/16 x 12-5/16"

- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2011.12

Essay by David Snowball, Professor of Communication Studies and Violet M. Jaeke Chair of Family Life

Nearly a century ago, any educated adult in the western world would instantly have recognized this scene. Most would have been furious. Heroic nurse Edith Cavell, condemned to death by a German military court on October 11, 1915, resolved to face death bravely. Walking to her place of execution, her nerves finally gave out and she collapsed. The captain of the firing squad, disgusted by her weakness and unmoved by her frailty, knelt and fired a bullet into her forehead. Mustachioed, fat soldiers in spiked helmets look on. One soldier, horrified at the event, covered his face with his hand. That act of cowardice later led to his execution.

Cavell's story was a sensation. The Times of London discussed Cavell in 45 articles in the three months after her execution. Her life was featured in two films (The Woman the Germans Shot and Great Victory, Wilson or the Kaiser?) before the end of the war. She was sanctified in two dozen books, bearing titles like The Martyrdom of Nurse Cavell: the life story of the victim of Germany's most barbarous crime (1915) and Nurse Cavell: the story of her life and her martyrdom (1915). King George V invoked her execution in a plea for more men to enlist; in the three months following, weekly enlistments in the British Army doubled ("Edith Cavell"). Outrage was widespread in Belgium, Italy and France, where posters and series of postcards were issued, depicting the scenes of her arrest, trial and execution. Historians identify this as one of the two stories that most enraged American public opinion against Germany (Kunczik 45).

This image constituted the back cover of Le Petit Journal: Supplément Illustré (1915, November). The title, which translates as "The Assassination of Miss Edith Cavell: A German Crime that Outraged the Conscience of Humanity," and the image were both typical of the coverage of Cavell's death. Any reader would immediately fill in the details. The image fit perfectly with what readers already knew was true, about German atrocity and about the Cavell case.

What they knew, unfortunately, was wrong. Cavell and 35 co-defendants were tried by the Germans for helping 200 wounded Allied soldiers escape German-controlled territory. (Imagine a Confederate court trying the organizers of the Underground Railroad.) Cavell guaranteed her death by volunteering a series of damning details at trial, and agreed that she was aware of the nature of her crime. She was shot by a firing squad, not an officer. She was a nursing school administrator, not an "angel of mercy." She did not faint. She was not a young blond. She did not wear a Union Jack over her heart or a nurse's uniform. The execution was at a firing range, long before dawn. No soldier looked away, none refused to fire, none were disciplined ("The Testimony of Pastor Le Seur").

The art of the propagandist is showing us what we already know to be true. The propagandist does not educate, but instead illustrates and crystallizes. Propagandists need not lie when they can lead us to lie to ourselves.