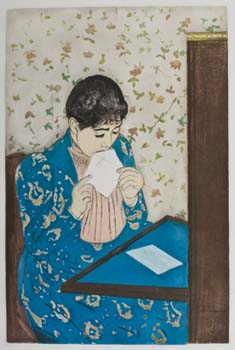

The Letter

- From the 1890-91 original

- Mary Cassatt (American 1844-1926)

- Color intaglio—aquatint and drypoint, published 1991 by the Bibliothèque Nationale

34.2 x 22.7 cm., 13-3/8 x 8-15/16" image

- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase through Gift of Lynn Jackson, Augustana College Vice President of Advancement, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2010.16

Essay by Dorothy Parkander, Professor Emerita of English and Conrad Bergendoff, Professor Emerita of Humanities

In 1890 Paris hosted a major exhibition of Japanese art featuring hundreds of woodblock prints. Here were "scenes of everyday Japanese life, usually in bold color and design" (Mathews 194). The prints mesmerized the American expatriate Impressionist Mary Cassatt. "I dream of doing it myself," she wrote after viewing the prints, "and can't think of anything else but color on copper." (Mathews 194). Cassatt had already won accolades for her drypoint prints, using only black ink, and she knew the challenges involved in the medium. Needle on copperplate allows for no mistakes, no corrections. "In drypoint," she said, "you are down to the bare bone, you can't cheat" (Sweet 117). But to advance to color affected both design and printing techniques-problems she solved with her usual ingenuity.

The famous color prints which wonderfully attest to her success are known as The Ten. Each of the ten compositions she inked by hand, and each, hand-inked, was duplicated twenty-five times (Mathews 196). Her friend and fellow impressionist Camille Pissarro, seeing her prints, was eloquent in appreciation: ".the tone even, subtle, delicate.adorable blues, fresh rose, etc." (Sweet 119). The Letter, one of The Ten, must surely have been in Pissarro's memory when he wrote of "adorable blues," for the color irresistibly invites the viewer to closer scrutiny. In a perceptive and stimulating appraisal of Cassatt's art, critic Frank Getlein comments, "In several important ways Mary Cassatt did in painting what Jane Austen did in prose fiction" (32). This insightful comparison offers a key to some of the delights to be discovered in this particular print.

The young woman here is not sitting for a portrait. She is authentic, she is herself, caught in a "private moment" (Getlein 82), a privacy which the enclosed space with its one-dimensional effect emphasizes. Desk and chair and close background wall secure her. The scene is internal in both physical and mental environments. But despite the secure enclosure, the lady's freedom is not restricted. Rather, the enclosure gives her power. In the very act of sealing her letter, she hesitates. Has she said what she intends in the way she intended to say it? She is not anxious or agitated, simply reflective. She seems to indulge in a personal assessment. Whatever her answer, she controls the choice as, in the social act of writing, she controls the discourse. Here is no mannequin but rather an Austenian woman—an Elizabeth Bennett, an Elinor Dashwood— a vital personality capable of trusting her judgments. Like Austen too, Cassatt gives precision of focus, no detail wasted or excessive. The blossoms on the lady's dress and on the wallpaper behind her—part of the Japanese influence—add a graceful, appealing femininity which softens the rigidity of vertical line and enclosure and lends the character charm as well as strength. And, of course, these details suggest the social class to which the letter-writer belongs. Cassatt chooses to depict, as Austen does, the world she knows. Her vision, like Austen's, is unsentimental, probing, and wholly engaging.