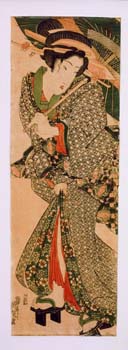

Courtesan with Umbrella

- ca. 1840s

- Keisai Eisen (Japanese 1790-1848)

- Color woodblock print

68.0 x 23.2 cm., 26-3/4 x 9-1/8" image

- Lent Courtesy of Dr. Thomas B. Brumbaugh Art History Collection through Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts

Essay by Joe Marusarz, Class of 2005 and Naoko Gunji, Former Assistant Professor of Art History

By the nineteenth century, ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world) focused on "the world of fleshly pleasure centering in the theater and the brothel" (Takahashi 9) and revealed a new "mature femininity, full of worldly wisdom" (Neuer and Yoshida 329). Such woodcuts created a modernist revolution in the second half of the nineteenth century, freeing Impressionists, Post-Impressionists and others from traditional illusionism established during the Renaissance.

Keisai Eisen's Courtesan with Umbrella represents one of the "decadent, coquettish women" (Neuer and Yoshida 330) typically depicted by this artist. Originally influenced by Katsushika Hokusai, Eisen ultimately developed a personal style based on new innovative color printing techniques (Takahashi 145). He was a court painter who is thought to have fallen from grace, and perhaps found his female models by running a brothel (Goebel 56). This particular woman is a well dressed courtesan in lavishly patterned clothing consisting of four different colors, necessitating multiple blocks for printing. She is likely holding an umbrella, not to protect herself from the rain, but more as a fashion statement. Her pose is complex, as she turns backward to view something behind her. As many ukiyo-e prints, Eisen's work projects an ideal beauty rather than a particular figure. The woodblock-print designers did not attempt to capture real likeness of models, but they created idealized women who were fully aware of the gaze of male audiences in the pleasure quarters which were secluded and different from the ordinary world.

The vertical format, often showing a single posed figure set against a blank background, developed from the traditional Japanese hanging scroll or kakemono-e (Wichmann 170-177). Unlike Renaissance one-point perspective, which draws the viewer's eye into the piece, the Japanese version leads the eye upward, as it was translated to the woodblock as a vertical pillar print. The effect was bold and unsettling to the establishment, but revealed new viewpoints to the avant-garde.