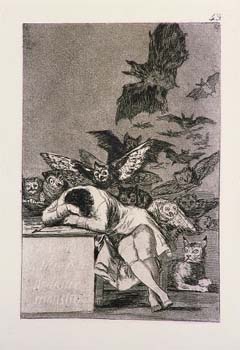

El sueño de la razon produce monstrous (The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters), from Los Caprichos (The Caprices)

- Etched 1793-1798, published 1799, posthumous printing

- Francisco José de Goya (Spanish 1746-1828)

- Intaglio

21.6 x 15.1 cm., 8-1/2 x 6" image

- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2000.21

Essay by Ruth Ann Johnson, Professor of Psychology

Goya's Sleep of Reason has generated varied interpretations. Of particular interest are those analyses that look within Goya's own psyche to examine his personal "demons" (e.g., despair over his failing health and disaffection with society) or generalize his work to the deeper content of the human mind (Dowling 331-332). Alford notes that "[t]he successful, aesthetic artifact, so successful that we call it a work of art, serves as a bridge between the artist and ourselves" (483). In this way, art may be seen as a statement of universal human experience.

Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis, proposed that people are motivated by innate, unconscious desires, just as instinctual drives guide the behavior of animals (Freud: A Life 35-36). Humans differ only in their ability to restrain and channel their instincts in acceptable directions, such as artistic expression ("The Origin" 214). Freud would agree with Goya that these animalistic or "monstrous" tendencies lie close to the surface of awareness, threatening the individual's sense of reality and self-control. Sometimes, however, unconscious impulses manage to slip into consciousness, as they do in dreams (201).

For Freud, dreams are "the via regia [royal road] to the interpretation of the unconscious" ("The Origin" 200). He believed that all dreams symbolically fulfill and partially satisfy the most basic wishes that people have learned to deny. Individuals remember only the dream's façade (what Freud called the manifest dream content), a disguise that hides the raw desires that churn within the unconscious. Freud referred to these unconscious desires as latent dream-thoughts ("Consciousness" 8-18). Although an ordinary dream signifies that these urges have been disguised successfully, "dreams which are apparently guileless turn out to be the reverse of innocent. . . they all show 'the mark of the beast'" (The Interpretation of Dreams 86).

It is not known whether Goya intended the night creatures to represent the artist's dream itself or to establish the dream's ominous mood. Either way, Freud would find the image closely tied to the primitive nature within all humans that constantly threatens to express itself-and sometimes succeeds.