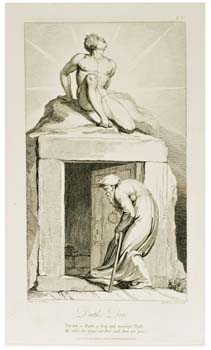

Death's Door, from The Grave, a poem by Robert Blair

- 1813

- William Blake (British 1751-1827), etched by Luigi Schiavonetti (Italian 1765-1810), published by Rudolph Ackermann (1764-1834), printed by Thomas Bensley (1760-1835)

- Etching, Plate III

29.7 x 17.5 cm., 11-11/16 x 6-7/8" image

Inscription: "Tis but a Night, a long and moonless Night, We made the Grave our Bed, and then are gone!"- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2009.5.c

Essay by Don Erickson, Professor Emeritus of English, Dorothy J. Parkander Professor Emeritus in Literature

Hardly any of the work for which we now consider William Blake a major Romantic poet and artist was widely known in his own time. His illustrations commissioned for an 1808 luxury edition of Blair's "The Grave" are an exception. This large and expensive book was dedicated to the queen, and had hundreds of wealthy, well-connected subscribers. It was Blake's most conspicuous success.

"The Grave" is a long meditation on death as a fearsome, gruesome leveler, and on the pains of suffering, loss, and grieving. Blair was a clergyman, and just before the poem's end he makes the turn one still hears at funerals toward the idea that death is an exit but also an entrance, and a new beginning. Blake's twelve illustrations focus on this last portion of the poem. Though the images are linked to specific lines, there is much more of Blake than of Blair in them.

In "Death's Door," for instance, both figures are versions of human forms Blake had drawn and engraved before, though never together on the same page. What do they represent? A now/then, body/soul narrative? The aged man entering the tomb certainly looks to be an image of mortality, and the youth above the door surely can be seen as the same man's immortal soul rejuvenated as it will be after his death.

But for prophetic, visionary Blake, eternity and immortality could suddenly be, at any moment, here and now. And the stages Blake was most careful to define and explore were not episodes in time but attitudes: ways of seeing and being, states of understanding and comprehension, parts of what he called Vision.

What attitudes do these two figures embody? The aged man looks strikingly like several other figures in Blake's poetry and art who bend, lean, or look down, in fear, despair, or denial, preferring darkness to light, down to up. And the nude male above belongs to a large family of Blakean figures who are radiant and new, arising, awakening, emerging like newborns, or opening like flowers. We might call such figures opposites; Blake's preferred word was "contraries." Innocence and Experience, he said, were "contrary states of the human soul," and "without contraries there is no progression." A more deeply Blakean response to "Death's Door" should perhaps notice tensions between the two figures, should see them as contraries, contending for our attention and empathy. Seen together in this way, the two figures may be drawing us into a kind of progression or expansion of perception, toward increasing identification with the open, bright youth who so obviously sees better, sees farther and more, . . . and not later, but immediately, right now.

Walt Whitman first saw "Death's Door" when he read Alexander Gilchrist's Life of William Blake in 1881. A decade later it was still in his mind, and he left instructions that his own tomb be made in its image. When he died, it was (Ferguson-Wigstaffe).