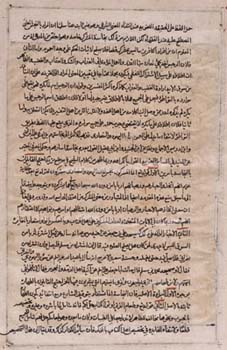

Page from the work title Madarik al-Ahkam by Muhammad al-'Amili, (d. 1600)

- ca. 1800

- Artist and calligrapher unknown

- Casein on vellum

23.1 x 14.9 cm., 9 x 5-7/8" image and text within framing lines

- Lent Courtesy of Private Collection through Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts, in Memory of Reverend Robert E. A. O'Connor

Essay by Cyrus Ali Zargar, Former Associate Professor of Religion, Islamic Studies

Depicted in these illustrations is a marriage of two worlds: Islamic jurisprudence and the court of Qajar Iran. The Qajars, fond of paintings depicting hunting scenes, also had a pragmatic interest in a particular method of interpreting Islamic law. This interpretive school, the Usuli School, emphasized rational derivation of law from scriptural sources, and it had only recently emerged triumphant after over a century of contending against a traditionalist school that frowned upon the use of individual reason in determining law, namely, the Akhbari School. The authors of the two books subject to illustration here epitomize this rationalist approach to Shi'i jurisprudence.

While the content of the discussions depicted (divorce and ritual purity) might seem technical or even bland, the victory of their legal approach might have been exciting enough to warrant the production of such books. It is interesting that the authors of these texts represent bookends, in a way. The first author, Muhammad al-'Amili (d. 1600), is earlier and emphatically rational. His more well-known name, "Author of the Madarik," derives from the work depicted here. The second, 'Ali Tabataba'i (d. 1815), lived either during or near the time of this production. While Tabataba'i was centered in Karbala, 'Iraq, his following as a doctor of law extended all the way to India, affirming the scope of influence such scholars had acquired by this time.

The illustrated manuscript echoes a time when book-making was not an industry, but an art. These lengthy productions were written entirely by hand, and beautifully so. One of these two compositions, in a contemporary printing, can span eleven volumes, which suggests the amount of work that went into their production. The calligrapher signs off at the end of this section that he wrote the manuscript "with my sinful, ephemeral hand, and I am the base servant Ibn Muhammad Ahmad, serving with pleasure." The calligrapher's signature at the end of one section or "book" signifies that, by this time, the artist as an individual has come to replace the artistic anonymity of the past. Working with a reed pen, the calligrapher aims to have a sense of regularity in the length and style of letters, to project beauty yet also lucidity, and, clearly also, to make a name for himself.

That a team of calligraphers, illustrators, paper-makers, and book-binders were commissioned to do projects of this sort is nothing new. It seems distinctive of the Qajar period, though, that they exerted such efforts for works of Shi'i religious law, as opposed to epic poetry, for example. It is intriguing that the images truly have nothing to do with the text at all. They are simply adornments indicating the quality of production. These manuscripts were likely produced for the Shah's court, so they needed regal pictures to make them suit their elitist audience, an audience that was probably not all that interested in the content of the text itself. Thus these illustrated manuscripts stand as visual representations of the intertwining of courtly and clerical interests, in a not-so-distant age when rulers relied on religious scholars for authority and even legitimacy.