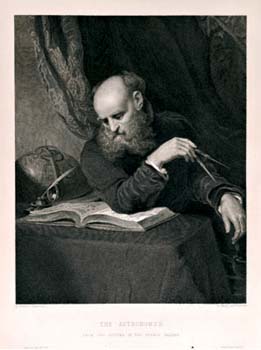

Galileo: The Astronomer

- After 1832 painting

- After Henry Wyatt (British 1794-1840) by Robert Charles Bell (Scottish 1806-1872)

- Engraving

24.4 x 19.6 cm., 9-5/8 x 7-11/16" image

- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College 2010.10

Essay by David Hill, Professor Emeritus of Philosophy

Galileo (born, 1564) learned to experiment with his father, a musician who worked with string lengths and tensions. He studied at Pisa, where he was appointed professor of mathematics. No record survives of his legendary study of speed of fall, involving objects of different weights dropped from the Leaning Tower, but it is the kind of thing he might have done. In 1592 Galileo moved to Padua, where he discovered the ratios that govern falling bodies, using inclined planes and rolling balls as his primary means of investigation. He found that as a descending body accelerates, speed is proportional to time of descent and distance covered to the square of the time. Galileo thus created a new method of science, the use of experiment and precise measurement to validate conclusions. For this reason he is often regarded as the father of experimental science.

In 1609 he heard about an optical instrument that made distant objects appear close. With high quality Venetian glass, he succeeded in improving the optics of the telescope, and in 1610 (Starry Messenger) he published his astonishing results: contrary to Aristotle, the Moon is not a polished sphere but is instead very much like the earth topographically; there are multitudes of stars never before seen; Jupiter has satellites of its own. He began to argue for Copernicus and against Aristotle. By 1615 this brought him into conflict with the Church, in the person of Cardinal Roberto Bellarmino, who in 1616 informed Galileo that Copernican theory could be used but not taught as truth, owing to conflicts with the Bible.

Seven years later a good friend and supporter of Galileo's, Maffeo Barberini, was elected Pope Urban VIII. Overjoyed, Galileo went to Rome and secured permission from Urban to write a book on Copernicus. The two men seem to have misunderstood one another. Urban expected that the book would be even-handed and would draw no firm conclusions—an exercise in assessing the evidence. Galileo wrote a pro-Copernican polemic (Dialogue on the Two Chief World Systems). Urban was enraged at this, and at the discovery that Galileo had treated some of his own suggestions with apparent contempt. Galileo was called to Rome, tried, and convicted of disobedience and vehement suspicion of heresy. He spent the rest of his life under house arrest, and is variously thought to be a martyr to science or an ingrate who betrayed his own patron.