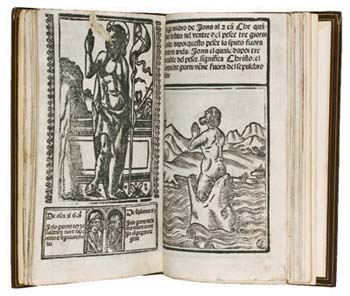

Opera Nova Contemplativa per ogni fidel christiano...or Biblia Pauperum, or Bible of the Poor

- 1516

- Engraved by Giovanni Andrea Valvassori detto Guadagnino (Venetian active 1510-1572)

- Woodblock book, or chapbook, printing ink on paper, modern brown morocco binding with contemporary-style blind tooling

15.8 x 10.5 x 1.4 cm., 6-3/16 x 4-1/8 x 9/16" sheet

- Lent Courtesy of Special Collections through Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts, Thomas Tredway Library, Augustana College

Essay by Sarah M. Horowitz and Jamie L. Nelson, Former Special Collections Librarians

Twenty-first century readers have become accustomed to the proliferation of information available on demand, but the transmission of information and knowledge has changed greatly over time. Before 1450, most books were handwritten, which meant that they were expensive and time-consuming to produce. Early books, termed manuscripts, are by their nature unique, since only one copy of each was ever made. Because these books were so labor-intensive and costly, they were prized possessions. Often including ornate multi-color and gold leaf decorations, such books are known as illuminated manuscripts. Manuscripts have their own conventions, such as the use of color (often red) or decorated initials to mark the beginning of a new or important section. Because of their great cost and scarcity, illuminated manuscripts were available only to the very wealthy elite. The manuscript seen here (web gallery 13A) is small enough to fit in the palm of your hand, indicating that it was made for personal use, probably for a wealthy woman. This text is commonly known as a "Book of Hours" and contains psalms and prayers written in Latin for Christian devotion.

The invention of moveable type by Johann Gutenberg around 1450 in Mainz, Germany, radically changed book production. Using moveable type and the printing press, more than one copy of a book was created at a time. This reduced the per-book cost, though books would remain too expensive for most individuals until the mechanization of printing in the early 19th century.

The Gutenberg Bible (web gallery 13B), or the 42-line Bible, was the first book printed with moveable type in the West. Early printers designed their books to resemble illuminated manuscripts, including conventions such as decorated initials (see the right-hand column of the Gutenberg page) and typefaces resembling handwritten script. Such flourishes eased the early transition to multiple-copy book production, and gradually books developed their own style and conventions separate from those of manuscripts.

However, printing did not instantaneously displace manuscripts. Intermediate technologies, such as block books (also called xylographica), were popular in the mid-15th century. Block books were essentially picture books, usually religious in nature, often aimed at educating the illiterate. There were several common texts used in block books, including the Apocalypse, the Dance of Death, and the Biblia Pauperum or "Bible of the Poor" (web gallery 13C), a comparison of Old and New Testament stories which was probably intended for less educated clergy. Although the wood used to carve the images and texts was cheaper than metal type, it was also less sturdy, so printers could not produce as many copies of a block book as with moveable type, but it was decidedly more efficient than handwriting individual manuscripts.

These three methods of text production highlight the technological overlap in the late 15th and early 16th centuries. Each of these three books was designed for a different use: the manuscript for personal devotion, the Bible (which is very large) for official use in a church or monastery, and the block book by someone learning or teaching biblical stories. Printers could utilize the different technologies based on the audience, purpose, and value of a book.

Books have continued to play a key role as purveyors of information, from the Renaissance and the Reformation to modern times. But books are also artifacts, providing contextual clues about the society that produced and used them. Looking at these featured texts in their original physical formats is a much different experience than looking at their texts reproduced on a screen, or repackaged in a modern paperback. The materials used and the process of their construction are evidence of the wealth, education level, daily life, and interests of the book's readers.

The three books shown here are among the earliest examples of the materials held in Special Collections—Augustana's collection of rare books, manuscripts, college archives, and local history ephemera. Many of our more "modern" materials are also unique, including letters, diaries, scrapbooks, and photographs which were created by individuals and organizations over the course of a lifetime. Each of these items tells its own story, partly through the recorded text and partly through the surrounding context.