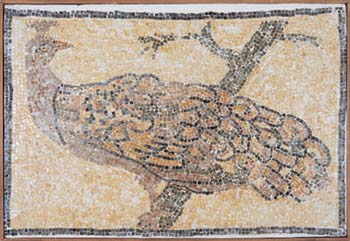

Pavo (peacock)

- 300-400 CE

- Artist unknown (Roman)

- Mosaic of lifted ancient tesserae fragments, restored with ancient tesserae, mounted in plaster

47.5 x 69.7 cm., 18-1/2 x 27-1/2"

- Catherine Carter Goebel, Paul A. Anderson Chair in the Arts Purchase, Paul A. Anderson Art History Collection, Augustana College, 2003.12

Essay by Thomas R. Banks, Professor Emeritus of Classics and Dorothy J. Parkander Professor Emeritus in Literature

This peacock, shown in mosaic, looks over his shoulder and proclaims the importance of provenance in looking at ancient art: Where did I come from? When exactly was I made? Alas, like so much of the portable ancient art we value, he surfaced in unknown ways. The Paraskevaides Museum believes the mosaic can be traced back only as far as an old English collection—i.e., it was not stolen, by current understandings—while it began life in the Roman world between 300 and 400 CE. Thus, in our ignorance, we can see three contexts for it, three possible meanings for Pavo.

One context to fit into such a broad span in time and area would be religious—the pagan beliefs and rites associated with the goddess Juno. The peacock was Juno's bird. For pagans the peacock was associated with reverance for the immortal goddess. Thus the emperor Hadrian dedicated a golden, bejeweled peacock at the temple of Juno near Mycenae (Pausanias 17.6).

A later religious context, the Christian, took up the peacock as a symbol of immortality itself, one to be known in the resurrection of the flesh. St. Augustine (ca. 350-430 CE—perhaps, that is, a contemporary of Pavo) asks us, "Who but God, the creator of all things, granted to the flesh of the dead peacock not to putrify?" (Augustine xxi.iv). Hence we may note the appearance in later Christian art of the peacock presaging the Resurrection of Christ (Ferguson 95).

A third possibility would be secular, perhaps from the decor of an opulent private home. For this bird could also be a symbol of luxury, as we read in the Satyricon of Petronius. There, the nouveau riche Trimalchio tries to impress his guests with an hors d'oeuvres tray shaped like a bird warming a clutch of eggs—peacock's eggs for them to eat (Petronius xxxiii). Pliny the Elder credits the orator Hortensius with first serving the peacock as food, in the first century BCE That occasion was a banquet celebrating Hortensius's inauguration into the college of the priesthood (Pliny the Elder 10.23).

Not knowing which if any of these provenances to choose, we are constrained to a bare museum description for facts alone. Nevertheless, those bare facts, and the fact of the artistry, still permit us to enjoy Pavo's handsome reappearance into the light in our century, immortal indeed.